I happened to be in Southern California (Palm Springs specifically) for work, and decided to extend the stay in order to check out the deserts over the lovely spring weekend. I had not been to Joshua Tree National Park since I had taken a trip with my high school over 15 years ago (Oh dear, was it really that long ago already?). Anyway, I did not remember much from the park other than camping there under the stars and waking up to watch the silhouette of a climber on top of a large granite boulder, back-lit by an amazing citrus colored sunrise. Unfortunately, I was not able to grab a campsite within the park this time, so I could not attempt to replicate that pleasant memory. But I was able to explore the park via 4×4 vehicle thanks to some awesome off-roading friends. And we took advantage of renting space on someone’s private land on the northside of the park.

Joshua Tree National Park is 1,235 square miles (that’s nearly 800,000 acres) of desert located in Southern California, directly east of Palm Springs. It is only a couple of hours east of Los Angeles, and there are multiple Southern California airports that are conveniently located even closer (in particular Palm Springs International Airport and Ontario International Airport), making this park easily accessible to those near and far. Unlike the parks located in alpine and mountainous regions, the summertime is the off-season in J-Tree because the temperatures are so extreme and not many humans find hiking in 100 degrees particularly pleasant. People opt for more mild climate regimes in the spring and fall, but it can also be a popular winter camping spot, especially around Thanksgiving and Christmas holidays. It is also a haven for climbers, but definitely check the National Park Service website for current conditions as many areas close due to nesting birds.

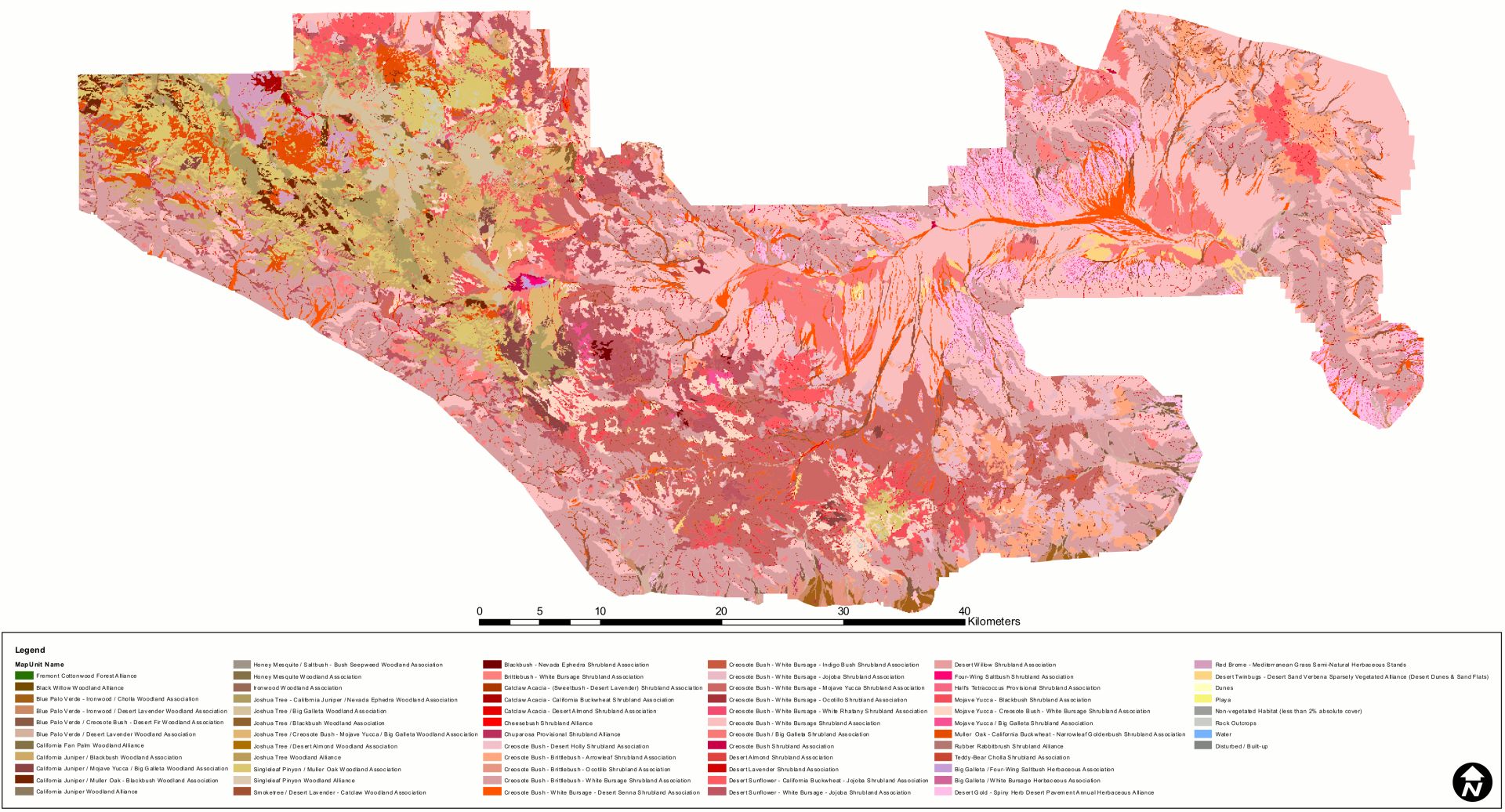

Many people think of deserts as being desolate and barren, but this is a common misconception. Deserts are teeming with life. As shown below in this vegetation map of Joshua Tree National Park, it is hard to find any non-vegetated area (displayed as gray) throughout the entire region.

Joshua Tree National Park encompasses two distinct desert ecosystems at different altitudes – the Mojave and the Colorado [1].

The Colorado Desert

On the eastern part of the park where the elevation is less than 3,000 feet and dry, plants such as cholla cactus, ocotillo, and creosote brush thrive. This sub-region of the park is part of the California’s Colorado Desert, which is a small piece of the greater Sonoran Desert that encompasses approximately 7 million acres [2]. This means that the California Colorado Desert is a piece of a desert that is about as large as the entire island chain of 137 islands that comprise the state of Hawaii!

Cholla Cactus Garden

During this trip we drove through Indio, waved at all of those attending weekend 1 of Coachella, and entered the park through the southern entrance. After a brief stop at the visitor center, our first stop was the cholla cactus garden. I feel like the Park System signs at the Garden did not adequately describe the true dangers of the cholla cactus.

What makes the cholla cactus so dangerous? Its prickly barbed spines readily detach, as if in constant anticipation of attacking anyone who accidentally brushes up against it. These barbs on the ends of the spines can cause more severe pain than the average cactus, as it affects more nerve endings in more tissue, and can readily rip skin as they are being pulled out. I have heard my fair share of horror stories that have ended in Emergency Rooms thanks to this plant, so please be careful!

As you walk in the designated path, you are at times completely surrounded by cholla.

As you walk in the designated path, you are at times completely surrounded by cholla.

When the cholla dies, its woody skeleton has a distinct pattern known as reticulate. The wood is often used to make canes or other souvenirs [3].

The Mojave

The western region of Joshua Tree that is slightly cooler, moister, and higher in elevation is in the Mojave Desert and home to the Joshua Tree (yucca brevifolia if you want to get all scientific and Latin) where the National Park derives its name. The Joshua Tree is a member of the Agave family, and was used by Native Americans to weave baskets/sandals and its seeds and flower buds were used as a healthy addition to their diet. Mormon pioneers traveling in the mid-19th century reportedly named the tree after the biblical character, Joshua, as the tree limbs appeared to be outstretched to the sky, guiding travelers westward to the promised land [4].

This region of the park also has some interesting exposed geology. The gigantic and varied granitic boulders are a major attraction to rock climbers. You don’t have to be a climber to climb around some of the boulders, as many trails show an easy way of getting on top of them. We stopped off at Skull Rock and had a great time wandering around boulders.

Geology Tour Road and Berdoo Canyon Road

If you are hoping to escape the crowds of the more popular rock attractions along the main highway, there are some dirt roads in the park that are less frequently visited. We took a 4×4 vehicle on the Geology Tour Road, and continued onto the Berdoo Canyon Road. This provides an alternate exit to Joshua Tree National Park, travels in the Little San Bernardino Mountains before ending in the Coachella Valley. The sign at the beginning were out of geology tour pamphlets, so we could only help but wonder what all of the little numbers along the road signified. The trail transports you through different granite typical of intrusive basement rocks, and jumbles of different sized sedimentary rocks (sedimentary breccia, more specifically). Apparently there are exposed faults within the valley, but I did not spot any, as I was more focused with securing the dog with the bumps in the back of the vehicle.

Nonetheless it was an excellent way to experience the park without the crowds, and we were able to let the dog roam free for a bit as there was less of a risk of cars passing. The first part of the road during good weather is accessible to anyone, and signs signify where 4WD is recommended. There were intermittent pockets of deep sand, and some rocky sections that required careful tire placement. My friend used his vehicle to pull a stuck 2WD truck in one of the more technical parts of the road. The park boundary follows the road down until you reach remnants of a Berdoo Camp which housed workers from the Colorado River Aqueduct Construction project in the 1920-30’s [5]. After you reach the paved part of the road, you are greeted with sounds of gunfire. The active shooting range and trash/debris covered in graffiti is a little startling as it’s such a stark contrast with the beautiful canyon through which you descended.

Make sure to check the weather forecast before you are in the park with no cell reception. This canyon could get very dangerous during flash flood conditions.

Hidden Valley

The Mojave section of the park also is home to many oases, a testament of the moister conditions within the desert. Hidden Valley day use area has picnic tables spread among the large granite boulders, which make a lovely spot for lunch. There is also a short loop trail, the Hidden Valley Nature Trail, that is full of desert vegetation and animals that feed on it. The 1.1 mile long trail begins where Bill Keys, a desert pioneer, blasted the rocks to improve access for his cattle in 1936 [6]. The natural valley surrounded by towering rock walls and large boulders funnels and traps rain, making ideal conditions for a range of plants and animals not typically found together to thrive in this section of the Park.

It is also a place for rock climbers to explore, assuming that particular rock wall is not inhabited by migratory birds.

Although it is more wet than other regions of the desert, keep in mind that it is still incredibly dry. Signs at the beginning of the trail remind you to turn back as soon as your water is half full. Even though the trail is only a mile long, there is sparse shade, and we both went through about 16 ounces of water despite it only being in the high 70’s/low 80’s.

Keys View

And lastly, if you want to just chill and drive to an amazing view of the valley, make your way up to Keys View. I imagine the view was named after that same desert pioneer who blasted a notch in Hidden Valley, Bill Keys. The viewpoint and parking lot is perched on the crest of the Little San Bernardino Mountains, and provides amazing panoramic views of Coachella Valley. Although rare nowadays, on a really clear and smog free day, you might be able to see to Signal Mountain in Mexico! To the left (south) you can see the Salton Sea, which sits at 230 feet below sea level, and shines in a bright white as the salt crystals reflect the blazing sun-rays. You can also see the Berdoo Canyon Road as it exits the canyon and makes it way to Coachella Valley. To the right (north) you can view Indio back-dropped by the Santa Rosa Mountains along with 10,800-foot San Jacinto Peak behind Palm Springs. San Jacinto Peak is the highest peak of the San Jacinto Mountains. Further to the right (north), the peak of 11,500 foot high San Gorgonio Mountain is observed usually snow-covered [7]. The southwest side of the ridge descends dramatically as it drops nearly a mile in elevation into the Coachella Valley below. The infamous San Andreas Fault system, a strike-slip fault that stretches 700 miles from Gulf of California to the Mendocino Coast and has been historically responsible for multitudes of damage and lost lives, runs through the valley below.

There are many sites still left to see that I didn’t even touch on during my couple of days spent in Joshua Tree National Park. But it was a whole lot of fun exploring regions that I didn’t know existed, and to witness the plethora of plants and critters that call the Park home.

Nicely done. Lots of good information.

Very great write-up and lovely photos. I still haven’t made it to Joshua Tree despite living in LA for 9 years now. Shameful! I will make it one of these days. I had an unfortunate run-in with a Cholla cactus in Arizona several years ago. I’m glad you warned people about them!

Thank you very much! You should definitely check it out. Now is a good time before it gets too hot. And yikes about the cholla. Those plants are fascinating and oh so painful.

Awesome post Kara. I want to find a cholla wood walking stick next time we go!

Thanks! And yes! They might have a Cholla walking stick at one of those shops in the town of Joshua Tree.

Kara, your article provides everything someone needs to decide if they would like to travel to Joshua Tree. Completely informative and your photography is truly beautiful. You write in a flowing, fully descriptive and easy to read manner. And now I know the origin of the name Joshua Tree!